In the Summer of 2000 I had the great pleasure of meeting James Gillespie, editor of The Clarinet Journal, during the International Clarinet Association (ICA) convention in Oklahoma. James asked me if I would like to contribute a regular column – an invitation that I found both humbling and daunting! The following ‘Letter from the UK’ was first published in March 2010 in The Clarinet Journal, the official publication of the ICA.

Let’s play that guessing game where you try to work out who I’m describing before I’ve given away too many clues. Here goes then: he’s a top, living, English composer who has written a lot of seriously important music for the clarinet including a concerto and a quintet. He belongs to the generation that counts Peter Maxwell Davies, Harrison Birtwhistle and Alexander Goehr among their number (all who have written for the clarinet but none as much as our mystery composer.) Have you got him yet? He lives in New York (and has done since 1979). He has also written some of the most effective film music in the history of the cinema. And he now lives for jazz and cabaret. You must have got him by now! I write, of course, of Sir Richard Rodney Bennett.

Born in Broadstairs, Kent in March 1936 (also incidentally the birthplace of Prime Minister Edward Heath) into a very musical family – mother was a pupil of Holst and a concert pianist and father was a singer, songwriter and librettist. Richard began composing when he was about 13 and wrote his first clarinet work at the age of 16. This was a Concertante for clarinet, strings and percussion, probably for a school friend. It remains unpublished at the present time but is an effective pointer of things to come. There is one highly energetic movement of what was clearly intended to be a longer work. Like so much of Richard’s early music it is written using the 12-tone system. The clarinet writing is idiomatic and quite difficult and he wrote it in just two days. Nine years later came Richard’s second work – a Quintet for Clarinet, String trio and piano. Richard was very much drawn into the music of Elizabeth Lutyens at this time and this quintet drew much from her style. 1965 saw the composition of a Trio for flute, oboe and clarinet. Written for the same combination as Malcolm Arnold’s Divertimento and similarly in six short movements. It’s quite a gritty work again written in a strict serial style – but highly effective in the right programme. It was first performed by Richard Adeney (who also played in the first performance of the Arnold), Peter Graeme and the great Gervase de Peyer.

Next (in August 1966) came the delightful Crosstalk for two clarinets. I wrote about the background to this gem in my June 2007 letter so to cut a longer story short: Thea King and Stephen Trier were in residence at the Dartington Summer School of Music (along with Richard). Thea was chatting to Richard about the need for more duets one evening and woke up the next morning to discover some sheets of manuscript paper slipped underneath her bedroom door. Richard had composed this gorgeous and inventive four-movement suite for her literally overnight! It was given its first performance that very day.

We then had to wait eleven years for the next work – 1977 and the Scena III for solo clarinet. But it was worth the wait - this is a significant work in the unaccompanied clarinet catalogue. It was first performed by Philip Edwards who told me recently, “I very much enjoyed working on it and played it often. It’s atonal in outline and both effective and memorable.” After an arresting opening it develops along slightly Messiaenic lines, inspired by the e.e.cummings quotation found at the start of the music, Then shall I turn my face, and hear One bird sing terribly afar in the lost lands. Lasting eight minutes it’s quite a substantial work. Published by Novello it’s easily available and really worth a look at if you don’t know it. Four years later Richard produced another unaccompanied work – one of his best known – the Sonatina for solo clarinet. A highly effective, tuneful and characteristic piece which was commissioned for the National Clarinet Competition for Young People in 1981. The competition was won by Alex Allen who “particularly loved the beautiful slow movement.” The Sonatina has often found its way onto examination lists but also makes for an engaging and audience friendly concert item.

Recollections on a Summer's Day

Jack Brymer and John Davies - Two great characters!

One of the delights of mid-August, when virtually the entire nation seems to go into hibernation, is that one can catch up and spend time with friends. I did exactly that recently. My teacher and mentor John Davies was staying with me for a few days and another good friend and clarinetist, John Holmes came to visit. The conversation, predictably, darted in and out of the clarinet world and (during lunch at a rather nice local Chinese Restaurant) it turned (for some time) to one of the clarinet’s great figures. Looking back over all my ‘Letters’ I was surprised to find how rarely he has appeared. He was someone of whom the three of us each had an interesting story to tell, so I am about to make amends. I speak of course, of the inestimable Jack Brymer.

John Davies first. John and Jack were friends for over fifty years but their first encounters were important for both. During the late 1930s they were living in Eastbourne on the south coast. Jack was teaching in a local school and John had a small dance band that played regularly in a department store (long since gone) called Dale and Kerley’s. Its tea-room was the glory of the town (especially during the summer season) and John would often employ Jack as clarinetist and saxophonist to fill the ranks. Jack would often ‘solo’ when they occasionally strayed into more modern jazz (rather than the palm-court fare that represented most of their repertoire.) Many years later, when John was senior clarinet Professor at the Royal Academy of Music he invited Jack to give a masterclass. In his introduction, John described Jack’s meteoric rise to fame (thanks to Sir Thomas Beecham) as ‘virtually happening in just a couple of weeks’. Jack’s responded (tongue firmly in cheek and with a sparkle in his eye) ‘I’d like to correct John – it was overnight!’

John Holmes is the Chief Examiner of the Associated Board, that global institution that provide graded musical examinations for (mostly) young developing instrumentalists and singers. John had the extreme good fortune to study with Jack Brymer. It all began when John took part in the Shell-LSO competition. Young players would be awarded the opportunity to sit in with the LSO and gain hugely useful experience. That particular year John wasn’t one of the few winners but Jack, in his very generous fashion, wrote personally to break the news. John plucked up courage (Jack after all was the most god-like figure in the clarinet world at the time) and wrote back asking for a lesson. He was in luck. Jack gave him his lesson and went on to teach him for the next five years.

John has many memories of Jack the teacher. He would be particularly exacting over the tone of chalumeau E. ‘If you can make that sound resonant, full and pure then everything else will fall into shape,’ Jack would say. One exercise was to stand in a corner of a room (or in a cupboard!) and play low Es. The sound would come back at you and you could really work at the quality. Another was to sing the pitch of open G then put the clarinet in your mouth and play it, then remove it and start singing again, then play it… repeating the process over and over again until you reach a stage where sung note and tone where virtually identical. Jack wanted to make you feel the clarinet was very much an extension of yourself. Interestingly Jack would make pretty much the same sound on whatever instrument he happened to be playing. And it would always be exceptionally well in tune.

They would work through the staple repertoire (with Jack continually offering fascinating insights and wisdom) and, from time to time, Jack would recommend less well-trodden works for study. The Krommer Concerto for example was a fairly new find around that time. Jack had discovered it whilst on tour in Japan (when it was spelled Kramar). John remembers being one of the first young British players to study and perform the work. He studied the Mozart Concerto too (which Jack would often perform up to two hundred – or more – times a year.) ‘ You must always imagine there’s someone in the audience who has never heard it,’ he would say. Sometimes they would play duets. Jack had one further (and lasting) influence on his young pupil. Outside the Brymer residence (in South Croydon) sat a gleaming Honda Superdream 400. It was the motorbike to have (and indeed allowed Jack to get around London and do twice as much as everyone else!) John still gets about on a motorbike to this day.

Finally to my Brymer story (and by far the shortest!) In fact I met Jack and heard him perform on a number of occasions, but the most memorable encounter was when I took my pupil Julian Bliss, (who was 8 at the time) to play to him. We drove down to Surrey and Julian played the Rossini Theme and Variations in Jack’s front room. Julian’s virtuosity was remarkable even then and Jack loved the performance. John Davies came too, and the two old friends enjoyed some very spirited reminiscing. It was all very special.

Jack didn’t record very much as a recitalist but (trawling the Internet) I’ve just found (and ordered) a copy of his famous ABK 16 –‘ The Voice of the Instrument: Jack Brymer playing Mozart, Weber, Schumann, Mendelssohn, Saint-Saens, Holbrooke, Hummel, Curzon, Arnold, Templeton and Poulenc.’ He always recorded in one take and John Holmes, who has the recording, tells me you can literally hear the fun that Jack was having in making this disc. I can’t wait for it to arrive - it will bring the sleepy month of August to a wonderful conclusion.

Tales from up north (or what made you take up the clarinet?)

In the Summer of 2000 I had the great pleasure of meeting James Gillespie, editor of The Clarinet Journal, during the International Clarinet Association (ICA) convention in Oklahoma. James asked me if I would like to contribute a regular column – an invitation that I found both humbling and daunting! The following ‘Letter from the UK’ was first published in March 2010 in The Clarinet Journal, the official publication of the ICA.

I’ve just spent a week in the lovely city of Edinburgh judging their annual music Festival. The quality of playing was very high - a stunning performance of the Lutoslawski Dance Preludes and a heartfelt Brahms E flat particularly stick in my mind.) But I want to pass on two delightful stories told to me by one of Edinburgh’s leading clarinet teachers, Pamela Turley. Both concern slightly unexpected ways of coming to the clarinet. Pam was a pupil of Thea King and now teaches at St Mary’s Music School (Edinburgh’s specialist college for young musicians up to the age of about eighteen) as well as Fettes College (where ex-Prime Minister Tony Blair went to school). She is also one of Scotland’s leading players. But how she came to play the clarinet is really rather enchanting.

As a young girl of about eight or nine Pam decided she wanted to learn a wind instrument. Her kindly mother immediately took her into the sitting room where lived the record player and the nearest record to hand happened to be Rossini’s William Tell Overture. Pam listened eagerly as the music unfolded until suddenly, ‘That’s the sound I want to make! That’s the instrument for me!” exclaimed the delighted young Pamela just as the beautiful Cor Anglais began its lovely solo. “That’s a clarinet,” announced her caring, but not quite accurately informed mother. So, after a number of phone calls it was discovered that an uncle had an instrument hiding away, unused, in a cupboard. Pam worked hard at her clarinet. “When will I start to sound like my recording?” she asked her teacher. Unaware of the very particular ‘clarinet’ sound Pam was craving for the two continued to work hard. After many more months of practice the frustrated Pam again declared to her teacher, “I’m still not sounding anything like it.” So the record was finally produced and the awful truth was revealed. Happily, Pam decided that the sound she was making on her clarinet was just a pleasing as William Tell’s Cor Anglais and she ended up a pupil of Thea King in London.

In fact Pam’s other story originates from Thea herself. The great Jack Thurston was giving a recital at Rugby School – one of England’s oldest and most celebrated independent schools. His pianist was of course the young (and multi-talented) Thea King. They proceeded through their recital evidently to the delight of the young Rugby boys who hadn’t been exposed to such virtuosic clarinet playing or musicianship. As the recital drew to its conclusion, Thurston finally spoke to his captivated audience. “Actually you know, the clarinet really is quite an easy instrument. Even my pianist can play it.” And he beckoned to Thea to join him in a seemingly unexpected (but in fact very well-planned) duet. Thea’s instrument was already set up and lurking behind a curtain. They proceeded to give a scintillating performance of the Poulenc double clarinet sonata. The boys were stunned and the next morning a surprising number queued up to see the Head of Music requesting that they begin clarinet lessons right away!

Taking up the clarinet in my case was the result of a letter from school offering lessons on the clarinet or violin. My earliest memory is actually of some disappointment when I discovered that my clarinet split up into small chunks. I was so looking forward to seeing the intrigued expressions of fellow passengers on my train to school as I sat proudly with what I thought would be an extremely long and mystifying looking case.

Readers will know that Edinburgh University owns both the exceptional Sir Nicholas Shackleton collection of clarinets (there is now a wonderful catalogue available) and also much of Pamela Weston’s collection of clarinet memorabilia. The immense amount of specialist knowledge that Nick had on his clarinets is now contained in the catalogue (which was largely put together by the excellent German writer and instrument expert Heike Fricke). This exceptionally lavish work is available from Edinburgh University at a very modest price. For those of you who with a thirst for clarinet history this is a must for your library!

© Paul Harris 2010 Reprinted by kind permission of the ICA.

Dentists and Dons

In the Summer of 2000 I had the great pleasure of meeting James Gillespie, editor of The Clarinet Journal, during the International Clarinet Association (ICA) convention in Oklahoma. James asked me if I would like to contribute a regular column – an invitation that I found both humbling and daunting! The following ‘Letter from the UK’ was first published in December 2009 in The Clarinet Journal, the official publication of the ICA.

I’ve recently been watching a repeat, on television, of the highly acclaimed 1976 BBC production of I Claudius. The imaginative and chilling theme music was by the Newcastle-born British composer Wilfred Josephs. It’s twelve years since Josephs died and his significant body of music for the clarinet still remains relatively unexplored territory to most players. So here’s a short introduction to some of these works which I hope will inspire you to have a closer look. You certainly won’t be disappointed.

Though Josephs was a keen musician as a boy his parents had no intention of allowing him to follow such a dubious profession. Consequently he trained to be a dentist, a career he pursued, probably somewhat half-heartedly, for a few years. But between drillings he was still quietly composing and after winning the occasional international composition competition was finally able to give up filling teeth and devote his life to music. He studied with a number of distinguished composers including Max Deutsch (a pupil of Schoenberg); but his style is rooted in a very accessible tonality and he constantly reveals, like Malcolm Arnold, a fine gift for writing lovely melodies.

His first major work for the clarinet was a concerto written for Keith Pearson (a pupil of John Davies) in 1975. Lasting just under half and hour and accompanied by quite a sizable orchestra it’s a large-scale work. Ten years later came a work equal in proportion to the concerto and one that should be in every clarinet players’ repertoire – a wonderfully atmospheric Quintet. Following in the tradition of the Mozart and Brahms it is for A clarinet and Josephs writes for the instrument with great skill and sensitivity. It was commissioned by and dedicated to Angela Malsbury (whose playing Josephs much admired). She gave the first performance with the Medici Quartet in August 1985. It has (perhaps uniquely) two first movements! The music is harmonically lush and full of gorgeous melody with a hint of rolling hills – but the landscape is never predictable and Josephs is continually taking the music around unexpected corners. The following scherzo is witty and charming and places considerable demands on the soloist (but they’re well worth the effort!) The slow movement is a magical, languid and heartfelt nocturne lasting nearly ten minutes, the occasional moments of disquiet preventing audiences from slipping into a dream-like semi-consciousness. The final movement is gently energetic and the work ends in a poignantly hazy mist reflecting the closing moments of the Brahms Quintet. Altogether a highly engaging work. Joseph also wrote Twelve letters of a Moral Alphabet (for speaker, clarinet, string trio and piano) a setting of words by Hilaire Belloc also for Angela Malsbury who has recorded it on the Unicorn label.

Again like Brahms, Josephs wrote two clarinet sonatas (in 1988) back to back: the ink was hardly dry on the first when he began the second. Both were written for Martin Powell and, like Reger’s Sonata in F sharp minor, use the A clarinet. The opening movement of the first Sonata (Op 148) is also Brahmsian in its soaring lyricism and occasional rhythmic ambiguity; there are also moments of ferocious energy. The meltingly tender slow movement is a jewel and the scherzo full of high jinks. The expansive melody that opens the final movement is simple and direct though the composer continually demands considerable reserves of technical virtuosity from the performer. The second Sonata (Op 149) begins in rather more dark and dramatic vein than anything we have heard in the first and its three movements (similar in general conception to the Brahms E flat) are more structurally concise compared to its partner. Both works are challenging to play but would delight any audience. The two Sonatas and the Quintet are beautifully recorded by Linda Merrick on the Metier label – do get to know them.

And clarinettists have still more to enjoy. There is an Octet that sits alongside Schuberts’; a delightful Old English Suite for the colourful combination of E flat clarinet, 2 B flat clarinets, basset horn and 2 bass clarinets and a Serenade to the Moon for 3 clarinets and bass clarinet. All in all quite a collection.

About the same time that I Claudius was first screened, children were enjoying a thoroughly charming new series centred around the fantastic adventures of a certain Mr Benn. I loved it - especially the music which, if the credits were to be believed, was apparently written by one Don Warren. But they weren’t to be believed. After some careful research I finally discovered that it was written by the well-known saxophone player Duncan Lamont, who wished to keep his duel life as a jazz artist and composer of children’s TV signature tunes separate! What particularly drew me to the music was the delicious main theme which was beautifully written and scored for bass clarinet and doubled on xylophone accompanied by a small ensemble. Duncan told me he’d originally scored the tune for trumpet, but the trumpet player failed to make the recording session and as there was a spare bass clarinet player about, he instantly re-scored it. Anyway, to cut a long story short I have just arranged and published (Queen’s Temple Publications, QT 118) ten pieces (including the superb title music) from the series for B flat clarinet and piano. They are absolutely delectable.

© Paul Harris 2010 Reprinted by kind permission of the ICA

A tribute to Pamela Weston (1921-2009)

In the Summer of 2000 I had the great pleasure of meeting James Gillespie, editor of The Clarinet Journal, during the International Clarinet Association (ICA) convention in Oklahoma. James asked me if I would like to contribute a regular column – an invitation that I found both humbling and daunting! The following ‘Letter from the UK’ was first published in September 2009 in The Clarinet Journal, the official publication of the ICA.

I’m sure that all readers will know of the very sad death of Pamela Weston. She had been suffering from the highly debilitating, enigmatic and still incurable condition known as Myalgic Encephalomyelitis (M.E.) for over seventeen years and had reached the point where life had become intolerable. In a deeply courageous and utterly determined manner, she decided to go to the Dignitas clinic in Switzerland and end her life.

I knew Pamela well, so the following is a personal tribute rather than an obituary-style record of her extraordinarily rich and influential life. Rarely does one meet someone who is at the top of their chosen vocation yet is also able to remain delightful, generous and modest. Pamela was such a person. And, to the enormous good fortune of all thinking clarinet players (as well as many others in the music world) she was driven by a powerful and relentless desire to know everything about the clarinet, about those who composed for it and those who played it, and then to share this information through her many wonderful publications. Many of these books on clarinetists of the past and present are unlikely ever to be superseded.

I first came across Pamela Weston’s name as a young student when I played pieces and studies from her various imaginative collections for beginner clarinetists. Many of these were published at a time when teaching material was all rather dry and academic. Teachers were no doubt delighted to find that someone had taken the trouble to make very playable arrangements of good music available. Pamela’s own musical beginnings were as a pianist and singer; surprisingly, she didn’t start the clarinet until her twenties. But she was plucky enough to persuade Frederick Thurston himself to teach her and things went very well. During the war years, she also had some lessons with the somewhat absent-minded Stephen Waters, about whom she had some amusing tales which, in her typically generous fashion, she shared with me when I was preparing my edition of Malcolm Arnold’s Wind Quintet (of which Waters played in the first performance).

My next, and much more significant encounter with Pamela was a little after my first book, The Cambridge Clarinet Tutor, was published. She gave it a lovely review in the Music Teacher Magazine and I decided I had to meet her. My teacher, John Davies, knew Pamela and arranged for us to visit her at home in the delightful Buckinghamshire town of Denham. It was a memorable visit. She was a fascinating host, the conversation was captivating and she signed my copy of Clarinet Virtuosi of the Past. It’s now a treasured possession. I remember once phoning Pamela to tell her that I’d spotted a copy of that very book in a second-hand bookshop for £260! She was really quite astounded.

Pamela’s enthusiasm for scholarly research into the clarinet’s repertoire has been unique. It was Pamela, for example, who first brought players’ attention to the fact that it wasn’t Wagner who wrote that beautiful Adagio. And then she went on to edit an important edition of the work. Her immensely carefully-researched Weber edition will surely never be replaced. And there are erudite editions of virtually all the major clarinet works as well as her friendly guide to teaching, The Clarinet Teacher’s Companion.

Pamela taught at the Guildhall School of Music for seventeen years during the 50s and 60s. She was a kind, thoughtful and witty teacher and produced many grateful students. She also performed widely at this time and had a number of works written for her. My favourite is the beautiful and highly evocative Three Songs of Innocence by Arnold Cooke which he wrote for her own and very successful Klarion Trio (consisting of herself, Jean Broadley and Eileen Nugent).

In recent years, Pamela and I have had regular chats on the phone as well as the occasional visit. I took John Davies to see her about four or five years ago. We met up in Eastbourne where both were brought up – though their paths never crossed in those now far off days. We went out to a wonderful fish restaurant and the animated conversation was full of wonderful recollections, though by then Pamela was beginning to tire quickly. I’ve driven down south to see her a number of times since; her enthusiasm for work never diminished.

About six weeks ago I was chatting to Pamela on the phone. It was early evening – the time of day she preferred for telephone calls – and she was her usual chirpy self. She had recently sent me her own concert programme of that historical first performance of Malcolm Arnold’s Second Clarinet Concerto, played by Benny Goodman. I had phoned to thank her for such a generous gift – I had no idea of its significance. We talked for a minute or two. The very next day I received a letter from Pamela with grim news, but it was touched with her own special sense of destiny; ‘Please don’t grieve for me as I am happy to go,’ she ended.

We spoke again a number of times after that, and on August 15th I received my last letter from her. She wrote of John Davies and Julian Bliss; of the performance of the Mozart Quintet which was eventually given just last night (as I write) in Edinburgh, by one of her former pupils, Philip Greene, who planned to start the concert with a moment’s pause in memory of Pamela. The letter ends in her customary positive and generous style, ‘It makes it all so worthwhile, doesn’t it? I was so lucky to have Thurston as a mentor and friend.’

She was much loved and will be profoundly missed.

Ben and Benn

I originally wrote this article for the September 2009 edition of the ICA Magazine. It turned out that someone had already written a piece that included background to the Britten Clarinet Concerto so instead of potential overlap I provided a completely new item. Here then is this previously unpublished article.

I always get excited when an interesting package drops through the letter box. A couple of weeks ago one such package did. It was the score of the intriguing ‘Movements for a Clarinet Concerto’ by Benjamin Britten, sent to me for review.

Readers may well know of the single movement, of which I have written about in a previous letter, which was recorded by Thea King in the early 90s: Movement for Clarinet and Orchestra on the Hyperion label with the English Chamber Orchestra.

Well now we have a whole concerto.

The story begins in 1941 when Britten was living in New York. The composer had attended a performance of the Mozart Concerto given by the great Benny Goodman. Soon after, the two met and Goodman gave Britten a strong indication that a commission was forthcoming (it would have followed his commission for the Bartok Contrasts) so, virtually straight away, Britten began serious work on the project. In March 1942 however, the composer returned to England and, extraordinarily, the manuscript was impounded by US customs officers as they thought some encoded secrets were hidden within the notation. Some months later, presumably after extremely careful scrutiny, it was eventually deemed safe and dispatched to Aldeburgh. But Britten was now working on Peter Grimes and though he did show some renewed interest in the concerto the following year it was soon filed away – regrettably never again to resurface during the composer’s lifetime.

Nearly fifty years later (in 1990) Colin Matthews (who worked closely with Britten towards the end of his life) completed the single movement which was subsequently recorded by Thea King on her disc of English clarinet concertos. More recently, Matthews had again been drawn to this fascinating work and contemplated reconstructing the complete three movements. The sketches contained nothing that would seem to suggest material for further movements so a more ingenious solution would have to be found. A little known work for two pianos, the Mazurka Elegiaca, which was written at almost exactly the same time as the first movement (the summer of 1941) was chosen as the basis for the slow movement. But what about the third movement? If the piece was to have stylistic cohesion then Matthews needed something else contemporary and appropriate. He went back to the original manuscript and was delighted to discover a substantial sketch for an unfinished orchestral piece (most likely the Sonata for Orchestra which features in a number of Britten’s contemporary letters). It was perfect material for the third movement. And so Colin Matthews set to and soon created the highly effective and engaging work of which I now have a copy on my desk.

The three movements last about seventeen minutes and are scored for clarinet and a large orchestra. The first performance was given by Michael Collins in May 2008 and it is now published by Faber Music. A recording is due out (on the Presto Classical label) in October this year (so should be available by the time you’re reading this!) It’s a great addition to the repertoire. Tuneful and very playable.

Now, some of you may still be wondering about to what exactly the ‘Benn’ part of the title of this letter was referring. Mr Benn is the eponymous hero of a charming children’s TV series. I loved it as a child - especially the music which, as the credits told us, was apparently written by one Don Warren. But in fact it wasn’t. After much careful research I finally discovered that it was written by the well-known saxophone player Duncan Lamont, who wished to keep his duel life as highly-acclaimed jazz artist and composer of children’s TV signature tunes separate. What particularly drew me to the music was the delicious main theme which was beautifully written and scored for bass clarinet and doubled on xylophone accompanied by a small ensemble. Actually Duncan told me he’d originally scored the tune for trumpet, but the trumpet player failed to make the recording session and as there was a spare bass clarinet player about, he re-scored it. Anyway, to cut a long story short I have just arranged and published ten pieces from the series, including the superb title music, for B flat clarinet and piano. (Queen’s Temple Publications, QT 118.) They are simple and absolutely delectable.

So, as we look towards the second decade of the twenty-first century the clarinet repertoire has become the richer through two memorable Bs: Benn and Britten.

Paul Harris 2009

Thurston's other pupil

In the Summer of 2000 I had the great pleasure of meeting James Gillespie, editor of The Clarinet Journal, during the International Clarinet Association (ICA) convention in Oklahoma. James asked me if I would like to contribute a regular column – an invitation that I found both humbling and daunting! The following ‘Letter from the UK’ was first published in May 2009 in The Clarinet Journal, the official publication of the ICA.

I’ve been reading a book about Stowe School recently. Readers may recall that Stowe is a grand and exceptionally distinguished eighteenth-century mansion set in a thousand acres of some of the best landscape gardens in the world, and I used to have the pleasure of teaching there. What really caught my attention (between cricket scores and the comings and goings of members of staff) was a performance of the Mozart Clarinet Quintet in March 1954, given by a promising young clarinettist by the name of Colin Davis. To most, Sir Colin Davis is the international conductor of immense stature. But he began life playing the clarinet and would probably have become a clarinettist of international stature had his interest in the baton not taken him in other directions. I decided to do a bit of detective work to see what I could find out...

Colin Davis began his clarinet studies at the age of eleven at Christ’s Hospital School. He was clearly a highly talented player. For example, the Director of Music (the composer C.S. Lang) organised performances of the Brahms Quintet when Colin was still quite a young teenager; one was at the house of Leslie Regan, a professor at the Royal Academy of Music. Christopher Regan (who went on to become Dean at the RAM) still remembers the performance, ‘Colin was already sounding very professional.’ His playing developed well, for he won a scholarship to the Royal College of Music in 1943 where he studied with the great Jack Thurston. Sir Colin recalls, ‘He was always encouraging: how fortunate I was to have had him as my first professor!’ Fellow student Judy Wilkins (who went on to marry conductor Charles Mackerras) remembers Colin Davis’s enviable ability to transpose, ‘I seem to recall that Colin only had one clarinet at the time, but he could easily transpose A clarinet parts, flute parts, anything really, onto the Bb in an instant!’ Indeed he regularly used to play Mozart Violin Sonatas with fellow student Peggy Gray and gave a memorable performance of the Kegelstatt Trio with Peggy and her future husband, Patrick Ireland, at the Goldsmiths Hall in London. Peggy remembers his wonderful musicianship and sweet tone, but what has remained even more strongly in her mind was the fact that during the course of that particular concert, Patrick’s trousers, to the astonishment of all, fell down!

One Christmas holiday during this period, the young Colin Davis joined another student clarinettist (and near neighbour) on Wimbledon Common to accompany a local choir in their seasonal carol singing. That friend happened to be a certain Pamela Weston and this was not to be the only time they played together. Colin Bradbury, also a student at the RCM, played with Davis around this time too, ‘The RCM supplied players to boost an amateur orchestra for a concert in Maidstone – I found myself playing second to Colin Davis.’

After the Royal College, Sir Colin was drafted into military service and joined the Household Cavalry where he played clarinet in His Majesty’s Life Guards Band. He was stationed in Windsor and the band played regularly at parades and events for King George VI. After being discharged in 1948, Sir Colin became quite a busy orchestral player. He played principal in the Kalmar Chamber Orchestra with either Thea King or Gervase de Peyer as second and, in 1949, toured with the Ballet Russes playing the Nutcracker in, among other places, a very cold Leeds. He also played with the London Mozart Players where he was reunited with his Wimbledon Common duo-partner, Pamela Weston.

Clarinettist Basil (Nick) Tchaikov remembers Colin Davis joining him to play second clarinet at Glyndebourne. It was a Mozart opera and Davis was clearly more fascinated by the conductor than the playing – a sign of things to come. They later performed together again in the New London Orchestra which was conducted by Alex Sherman (a conductor who notably worked with Segovia).

The next few years saw Colin Davis establish an important career as a leading player. He often performed with violinist Erich Gruenberg who said that he played with a lovely clear sound and was indeed an equal of his distinguished contemporary Gervase de Peyer. In 1951, Colin Davis famously gave the first performance of a new Sonatina by the young Malcolm Arnold at the RBA Galleries in London. The second half of the concert included the Brahms Trio. During the summer months, Sir Colin would often attend one of the great (eccentric) institutions of British musical life, Music Camp, where regularly, enthusiasts gather and camp on a hill (near High Wycombe in Buckinghamshire) and play music all hours of the day and night in barns. Particularly memorable were a number of performances he gave of Shepherd on the Rock with his then wife, the singer April Cantelo and, again, The Mozart Quintet. Dartington was also the venue for another performance of the Mozart which Sir Colin played with the Amadeus Quartet. Christopher Finzi recalls a moving performance of his father Gerald Finzi’s Concerto given by Sir Colin with the Newbury Strings (Christopher was a member of the cello section at the time) – the soloist was not phased at all by the fact that Gerald lost his place at one point, and they had to begin again.

Some of the final performances Sir Colin gave were recalled by the writer David Cairns, who heard him play both the Mozart and Brahms Quintets to a group of friends at a house belonging to the famous writer and traveller, Nick Wollaston in 1960. There was also a performance of the Schubert Octet, with the great cellist Jacqueline Du Pré. But as time progressed, Sir Colin’s international career as a conductor grew and flourished and the clarinet remained sadly idle in its case. We’ll never know quite how beautiful that performance of the Mozart Quintet was that March at Stowe; in fact as far as I can tell there are no recordings of his playing. Although we do of course have the wonderful recording of the Concerto played by Jack Brymer and the LSO conducted by Sir Colin – so, perhaps with a bit of imagination...

(In researching this article I have spoken to some wonderful people and I would like to record my thanks and their names here: Colin Bradbury, David Cairns, Christopher Finzi, Livia Gollancz, Stephen Gray, Erich Gruenberg, Peggy Ireland, Anita Lasker, Jean Middlemiss, Gervase de Peyer, Christopher Regan, Nick Robinson, Delia Ruhm, Lenore Reynell, Nick Tchaikov, Pamela Weston and Judy Wilkins.)

A forgotten partnership

In the Summer of 2000 I had the great pleasure of meeting James Gillespie, editor of The Clarinet Journal, during the International Clarinet Association (ICA) convention in Oklahoma. James asked me if I would like to contribute a regular column – an invitation that I found both humbling and daunting! The following ‘Letter from the UK’ was first published in March 2009 in The Clarinet Journal, the official publication of the ICA.

So much of the clarinet repertoire has been born of the collaboration between performer and composer: Stadler and Mozart, Baermann and Weber, Muhlfeld and Brahms are of course the most renowned. But there is a much less well-known relationship that blossomed during the second half of the twentieth century and produced an important collection of clarinet works.

To locate one half of this partnership we need to travel to Scotland, and find a composer whose considerable body of clarinet music richly deserves rediscovery. The composer in question is Iain Ellis Hamilton (1922–2000). And the clarinettist was fellow student and close friend, John Davies. The two young musicians met at the Royal Academy of Music in 1947. At first they formed a clarinet/piano duo, working their way through most of the repertoire. But Iain was there primarily as a composer (a student of William Alwyn, who himself wrote a very effective clarinet sonata) and soon began working on a series of important works for John. These works are now almost completely (but certainly unjustly) forgotten.

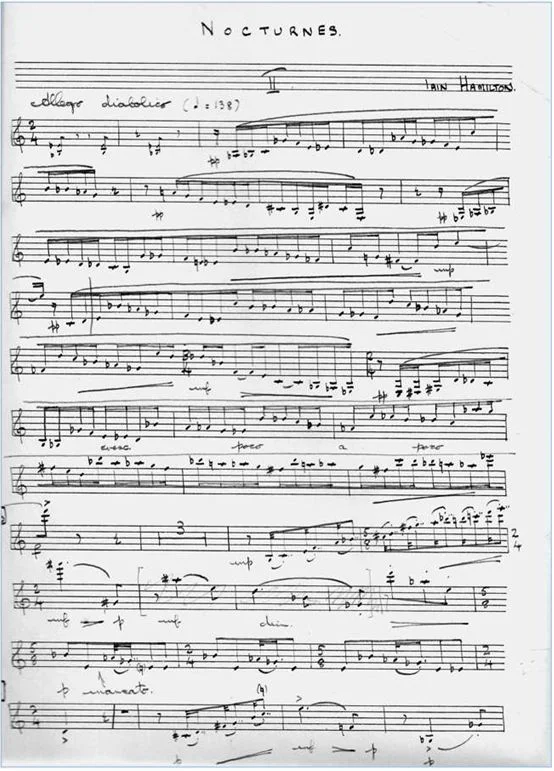

John Davies remembers, ‘He was a tremendously serious and energetic man; worked 48 hours a day. I don’t think he ever went to bed – he couldn’t stop!’ The violinist Nona Liddell found him ‘a little nervy, but very warm-hearted – a true Scot!’ He and John gave recitals all over Europe: Brahms, Ireland, Hindemith, Bax and Weber’s Silvana Variations were among their favourites. I now have the (well-annotated) copies they used in my own library and they offer many insights. A year after their meeting, Iain composed his first work for John; a clarinet quintet. John gave the first performance with the Liddell Quartet (led by Nona Liddell. ‘And a jolly good work too!’ she told me enthusiastically at a recent meeting.). John later broadcast it on BBC radio with the Aeolian Quartet in 1950. Though very interested in the latest serial composers, Iain’s own style at this time was more an amalgam of Bartók, Berg, Hindemith and Stravinsky, giving his music both rhythmic drive and a vivid harmonic colour. Next came his Three Nocturnes for clarinet and piano – perhaps his best known work. John gave the first performance on BBC Scottish radio in 1950 with Iain accompanying. The first London performance was given by Jack Thurston in 1951. They challenge a little, but are enormously worthy of study and performance: atmospheric and audience friendly.

In fact John and Iain regularly gave recitals in Scotland, at the central library in Edinburgh. These concerts were organised by Tertia Liebenthal, who also happened to be a passionate cat lover. Not only did Tertia arrange the concerts, she also reviewed them for The Scotsman, under the pseudonym Zara Boyd (her cat’s name). One evening however, the concert series came to a sudden and abrupt end. She and Iain were in a taxi making for the venue – they were late and John was already waiting uneasily. On the way, Tertia spotted a cat in distress by the roadside. ‘Stop the taxi!’ she demanded, the cat’s rescue now taking unquestionable priority over the concert. Iain was unhappy about this further delay and in his anxiety maliciously announced to the cat lover that ‘John had eaten cats you know, when he was a prisoner of war.’ It was to be their last engagement at the Edinburgh library...

Later in 1951, back in London with cats now forgotten, Iain composed his virtuosic Clarinet Concerto which won the prestigious Royal Philharmonic Prize. Though written for, and dedicated to John, it was Thurston who gave the first performance with the RPO. Jack Brymer gave the first broadcast performance. A Divertimento for clarinet and piano came next in 1953, followed by the Clarinet Sonata, once again dedicated to John, who gave the first performance in Paris in 1954. In 1955 came both a Serenata for clarinet and violin, written for John and Frederick Grinke (displaying a move to a more severe serial style) and the Three Carols for six clarinets, which Iain wrote for a group of John’s students at the Academy: fascinating, imaginative and useful arrangements (published by Queen’s Temple Publications).

In 1961, Iain moved to America where he became Mary Duke Biddle Professor of Music at Duke University in Durham, North Carolina. He was also was composer-in-residence at the Berkshire Music Centre at Tanglewood, Massachusetts (in the summer of 1962). He was to remain in the U.S. for twenty years, writing many wind chamber works among his large output.

There was a long break before Iain turned once again to the clarinet. And it was to be for the last time. In 1974 his opera The Catiline Conspiracy was receiving its first run at the Scottish Opera and, in the pit, playing principal clarinet, was the young Janet Hilton. She was enjoying the work so much that she personally commissioned Iain to write a new work. He wrote her his second quintet, evocatively entitled Sea Music. Janet gave the first performance at the Bath Festival with the Lindsay Quartet. Like all Iain’s clarinet music, the work provides a certain challenge for the performer, but it is more lyrical and rhapsodic, more tonal than some of his earlier works. Janet remembers that the composer took a lot of interest in the rehearsals and seemed particularly pleased with the performance. The London Observer called it ‘an attractive score, full of brilliance and light’. Most of these works are available from Theodore Presser Company.

Looking through the Iain Hamilton manuscripts in preparing this article, I found something amongst them that sent a real shiver of excitement tingling down my spine! I’m working on the Mozart concerto for a performance soon and had been giving quite a bit of thought to the whole business of cadenzas. What I found, most providentially, was a single sheet of manuscript paper on which Iain had composed three intriguing cadenzas for the Mozart; two for the first movement and a beautiful third for the slow movement. I now know exactly what I shall be doing for cadenzas!

The first manuscript page of the second Nocturne. Those who know the work will notice a significant adjustment of metronome mark and various other interesting alterations (including the deletion of three bars).

Four short pieces?

In the Summer of 2000 I had the great pleasure of meeting James Gillespie, editor of The Clarinet Journal, during the International Clarinet Association (ICA) convention in Oklahoma. James asked me if I would like to contribute a regular column – an invitation that I found both humbling and daunting! The following ‘Letter from the UK’ was first published in December 2008 in The Clarinet Journal, the official publication of the ICA.

I’d like to begin with a postscript to my last letter, on the subject of Pauline Juler and Howard Ferguson. I have come across some fascinating letters between Ferguson and Gerald Finzi. The two had an enduring and deep friendship which began in 1926 and ended with Finzi’s death in 1956. Readers will know Ferguson’s delightful Four Short Pieces. But you may not know that, like the Finzi Bagatelles, there were originally five of them! On January 1st 1937 Ferguson wrote to Finzi, ‘there is a set of five short pieces for clarinet and piano which I would like your opinion on: they are very slight, but well enough in their way, I think, and I would like to know whether you think they merit publication…I have asked Pauline Juler to tootle them through with me on the 12th for your especial benefit.’ Sometime between January and June, one of the movements, a ‘bubbly Rhapsody’ was omitted. ‘Not because I don’t like it musically,’ Ferguson wrote to Finzi on June 10th, ‘but because it seems impossible to play without making the most frightful clatter with the keys. Thus the set will consist of Four instead of Five pieces.’ So, did we perhaps lose a piece of our all-too-limited repertoire because Pauline’s clarinet needed a little oil? However, the movement later re-surfaced as the second of the Three Sketches for flute and piano Op. 14 (published by Boosey and Hawkes). But a letter from January 1938 suggests that we may be the poorer for something on an altogether larger scale. Finzi to Ferguson: ‘Pauline Juler is quite right in wanting you to do a Clarinet Sonata. I think you’d do it to perfection, and then there would be no need to revive Stanford and Bax. The little pieces are a signpost.’ How disappointing that he didn’t take the advice.

I try to follow the progress of my old pupil Julian Bliss as best I can, and heard two of his performances recently. I was delighted to hear him play the bittersweet Malcolm Arnold Second Concerto with the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra a couple of weeks ago, in the lavish Birmingham Symphony Hall. I remember working on it with Julian when he was only eight. He gave an astonishing performance even then, with the Huddersfield Symphony Orchestra, attended by Sir Malcolm himself. Just last week, Julian played Weber’s Second with the Ulster Orchestra in Belfast, which I picked up on the radio. It was a real virtuoso presentation with many imaginative moments. So many players worry too much about sticking religiously to the text and whilst Julian didn’t do anything outside the bounds of stylistic decency, there were lots of unexpected and delightful twists and turns causing one to think, ‘Yes! Of course! Why didn’t I think of that?!’.

I always love it when the postman has to ring the doorbell with a parcel too big to fit through the letterbox. And I was especially pleased recently when that parcel was Pamela Weston’s latest book, Heroes and Heroines of Clarinettistry. It’s a collection of many of her writings over the years – absolutely fascinating articles in which Pamela reveals many new insights into composers and works we thought we knew. It’s published by Trafford Publishing (with a Foreword by the ICA’s own James Gillespie) and should be in every clarinettist’s library.

I was judging a concerto competition the other day and was yet again astounded by the standard of young players today. All the musicians were under twenty (some well under) and we had more than adequate performances of Mozart, Weber and even one Nielsen! I remember rushing out to buy a copy of the Nielsen Concerto when I was about sixteen – after hearing a performance on the radio by the great Stanley Drucker. But I never really considered playing it at that time. Now I have my fourteen-year-old pupils wanting to learn it! That’s progress.

Great goings-on in the war years

In the Summer of 2000 I had the great pleasure of meeting James Gillespie, editor of The Clarinet Journal, during the International Clarinet Association (ICA) convention in Oklahoma. James asked me if I would like to contribute a regular column – an invitation that I found both humbling and daunting! The following ‘Letter from the UK’ was first published in September 2008 in The Clarinet Journal, the official publication of the ICA.

A friend sent me an old concert programme recently that really got my antennae buzzing! The concert in question took place on Wednesday, August 19th 1942 at the National Gallery in London. In fact between October 1939 and April 1946, the great pianist Dame Myra Hess was responsible for organising nearly 1,700 concerts at the National Gallery. The war had caused the gallery to close and all the paintings were moved out to a secret location, with the exception of one painting each month which was put on special show. But Myra Hess had the inspired idea of using the space for daily chamber concerts in order to lift the spirits of the beleaguered Londoners. It worked; many thousands came each day to hear the concerts and were indeed inspired by their message of hope.

This particular concert featured, as so many did, Hess herself, on this occasion playing Mozart’s Sonata K.331, followed by the great Serenade for Thirteen Winds. The players involved (under the collective title of The London Wind Players) reads like a music-historian’s dream. The two clarinettists were Pauline Juler and George Anderson. Pauline is well known for her early and impressive performances of the Finzi Bagatelles which inspired the composer to write his Concerto for her – but she never played it. Pauline was about to get married and she decided to give up playing the clarinet for good. She was the daughter of an Harley Street doctor and, by all accounts, a musician of charm and wit. But she did suffer from frequent memory lapses; ‘my forgettery’ as she called it. Pauline Richards, as she became, lived out her life in the delightful Suffolk village of Pakenham and died in 2003. (More about Pauline later.) The other clarinet player was George Anderson, a pupil of Henry Lazarus, who although seventy-five in 1942, was still teaching at the Royal Academy of Music. In fact he remained there until his death in 1951 and taught, among many others, John Davies and Georgina Dobrée.

The two bassett horn players were Walter Lear and Richard Temple-Savage. Lear, like so many clarinet players, enjoyed a very long working life. He was professor of clarinet at Trinity College of Music for fifty years and played, intermittently, at Covent Garden for seventy-one years! It is thought that he might have given the first performance of the little known York Bowen Phantasy Quintet for Bass Clarinet and String Quartet. (Readers will find much concerning Temple-Savage in my article of May 2005.)

The horn section appearing on that memorable concert date also boasted some very well known names: Dennis Brain, Norman del Mar and Livia Gollancz. Livia (daughter of the publisher Victor Gollancz and still very much alive) was a direct contemporary, fellow student and friend of Sir Malcolm Arnold.

Talking of Sir Malcolm, the Third Arnold Festival is just around the corner, in mid October. As usual his clarinet works will be represented: this time it’s the late and compelling Divertimento for two clarinets (played by two of my pupils, Charlotte Swift and Jonathan Howse) and the miniature Fantasy for Clarinet and Flute (written about the same time as his haunting score for Whistle down the Wind and bearing many resemblances).

And so back to Pauline. A number of years ago I was sent an interesting work, which I’m ashamed to say has lingered in my ‘awaiting action’ pile for some time. It’s a big neo-romantic clarinet sonata by Charles O’Brien. I finally played it the other day and discovered it to be very much worthy of attention. O’Brien was a Scottish composer born in 1882 (two years before Brahms wrote his Opus 120 sonatas). Though written about fifty-five years later in 1939 it is in fact quite Brahmsian in style (or perhaps ‘Stanfordian’) and is in the wonderfully appropriate clarinet-friendly key of E flat. It turns out that O’Brien first sent it to Pauline for her recommendations. She evidently suggested a major revision of the final movement and that is now the published version (The Hardie Press, Edinburgh). But she didn’t give the first performance. That privilege was entrusted to Keith Pearson (another John Davies pupil) who recorded it for the BBC in 1966. There’s nothing too technical in it, so if you have a place for a big romantic sonata, do give this a go!