In the Summer of 2000 I had the great pleasure of meeting James Gillespie, editor of The Clarinet Journal, during the International Clarinet Association (ICA) convention in Oklahoma. James asked me if I would like to contribute a regular column – an invitation that I found both humbling and daunting! The following ‘Letter from the UK’ was first published in December 2005 in The Clarinet Journal, the official publication of the ICA.

I recently gave a performance of the charming Beethoven Trio for clarinet, cello and piano. The combination works well and it’s therefore surprising that so comparatively few composers have seen the potential for the dark brooding colours, passionate melodies and the kind of energy that the three instruments can conjure. There are one or two British works worthy of study: Benjamin Frankel’s Trio Op. 10 is now sadly out of print but available from libraries. (His quintet, written in 1956 for Thea King, is a haunting work. Thea’s recording of it on Hyperion’s collection of English Clarinet Quintets should be in everyone’s library). There is an interesting work (especially for American readers) by the lesser-known Kenneth Leighton: Fantasy on an American Hymn Tune Op. 70, written in 1974 for Gervase de Peyer and published by Novello.

But the reason I’m taking you down this particular avenue is because a fascinating manuscript has just come into my possession. It did receive a first performance, but has been lost, hidden away in a box in a cupboard for nearly fifty years. It is a Trio for clarinet, cello and piano by Malcolm Williamson, the late ‘Master of the Queen’s Music’ who died in March 2003. Williamson’s life was as colourful as his near contemporary Malcolm Arnold. He wrote symphonies, operas, ballets and a considerable amount of other music in just about every genre (including the music for two Hammer Horror films!). But his name is now virtually forgotten. Clarinet players ought at least to know his Pas de Deux for clarinet and piano; a delicious movement taken from his Pas de Quatre for flute, oboe, clarinet, bassoon and piano and published as a ‘stand-alone’ solo. The work was written in 1967 for the Metropolitan Opera Ballet and first performed at the Newport Festival, Rhode Island.

As far as I know, the Trio was given just one performance at the Aldeburgh Festival in 1958 before it disappeared. The performers were Harrison Birtwhistle (clarinet), John Dow (cello) and Cornelius Cardew (piano). Quite a line up! It is dedicated to Imogen Holst (Gustav Holst’s daughter) and is cast in one continuous movement marked ‘Poco Lento’. Birtwhistle (who studied the clarinet at the Royal Academy of Music with John Davies) must have had some technique, as much of the part is in the highest register (up to top B flats), often as short tongued notes marked down to ppp! Williamson was, at that time, experimenting with serial music; this piece however looks to be firmly rooted in F minor and explores the sonorities of all three instruments in a colourful and imaginative way. It looks a fascinating piece and certainly an intriguing addition to the repertoire.

A slightly later work is the Concerto for Wind Quintet and Two Pianos, composed in 1964 and published by Weinberger. It’s a sturdy work, technically and musically demanding, but very much worthy of performance. Next year is the 75th anniversary of Malcolm Williamson’s birth (he was born on November 21st, 1931) and there are going to be quite a number of performances of his music in the UK.

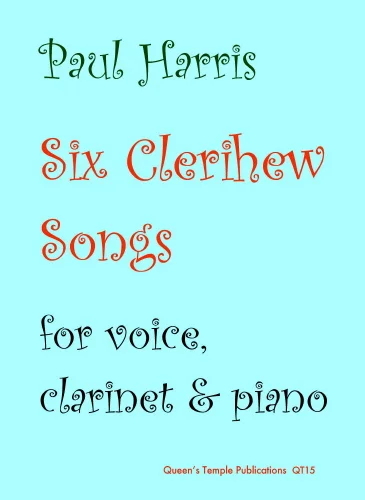

On another note, I received a very pleasant package the other day. It was a recording of a voice, clarinet and piano recital given in Kenmore, Washington, by American clarinettist David Frank. He had included Malcolm Arnold’s lovely song Beauty haunts the Woods and my own Clerihew Songs as well as many other works for the combination. And talking of Malcolm Arnold – it’s his 85th birthday next year! I hope many of you will be featuring his music to celebrate this. Do let me know and I shall pass the news on; he’s always absolutely delighted to hear of performances.