In the Summer of 2000 I had the great pleasure of meeting James Gillespie, editor of The Clarinet Journal, during the International Clarinet Association (ICA) convention in Oklahoma. James asked me if I would like to contribute a regular column – an invitation that I found both humbling and daunting! The following ‘Letter from the UK’ was first published in March 2007 in The Clarinet Journal, the official publication of the ICA.

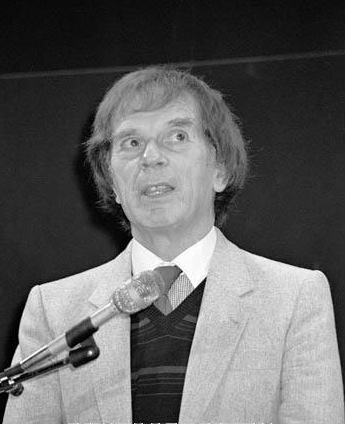

I picked up the eminent clarinettist Karl Leister from Luton Airport very late on Friday night. It was cold and windy and, as expected, the flight was delayed. We arrived home well after midnight, but Karl was full of life and determined to chat well into the small hours. We spoke of practice – eight to ten hours a day were no stranger to the young Karl. (I’d never topped about four!) Karl also showed me the artwork for his latest CD: a set of seven of Lefèvre’s delightful sonatas (edited by myself and John Davies) which should be appearing in the next few months on the Camerata label. And we spoke about John Davies, whose forthcoming birthday had really inspired this visit. (John had often invited Karl to give masterclasses when he was senior clarinet professor at the Royal Academy of Music, and they had become great friends.)

On Saturday, four of my pupils came to work with Karl. A lifetime of extraordinary musical experience has made him one of the greatest of masterclass leaders. I’m sure we’ve all sat through many such events. Sometimes the ‘master’ has interesting points to make, sometimes not. Sometimes the master can relate to the students, sometimes not. Sometimes the master likes simply to show off or tell stories – neither of which are of much help to the students, entertaining though this might be. But Karl is a true master of the art. No information is surplus to requirements. He is helpful, supportive, inspirational, and very much to the point. There is no doubt he has thought hard and deeply about music, repertoire and the art of clarinet playing. We had Debussy and Spohr, Mozart and Weber: all solid stuff, with Karl suggesting a new way forward for some phrase, or a particularly apt metaphor to provide deep insight into some colour or character. Karl’s views on technique too are very creative and we discussed many fascinating fingerings and styles of articulation. An occasional demonstration in his inimitable style helped underpin a point. These were never laboured or over-done. Ben, the youngest of my pupils, played the third movement of the Reger A Flat Sonata. This is a real favourite of mine (and perhaps the sonata I’ve performed most often). Karl was particularly excited about this. Like Karl, I’ve never understood why people don’t play the Reger Sonatas more often. Yes they do need a good pianist, but they are by no means turgid and heavy-going – the unhappy reputation they seem to have acquired.

In the evening we met up with a conductor friend of mine and went out for a meal and to chat, predominantly, about Karajan. All pupils having now left, Karl indulged himself in a night of fascinating story-telling about his many years with the Berlin Philharmonic, working with great conductors (their foibles and idiosyncrasies) and his exceptional experience of music-making at the highest levels.

Karl wanted something special to play for John’s birthday on Monday so on Sunday I was up at the crack of dawn composing a celebratory duet! As well as my new duet, Karl decided he’d like to play a couple of pieces with piano. So I introduced him to my new collection of repertoire pieces just published by Oxford University Press – Music Through Time Book 4; all pieces, as yet, unperformed! First of all we decided on an arrangement I’d made of the lovely Mendelssohn Song Without Words Op. 67 No.2.

And so to the second choice: to my considerable amazement, Karl chose a work of mine from this collection – perhaps my most frivolous piece yet: Fantastical Micro-variations on a theme by Mozart (the theme in question being the first subject of the Clarinet Concerto). In this outrageous piece, Mozart’s wonderful tune is paraded somewhat roguishly and irreverently through a number of shocking disguises – as a can-can, a tango, a beguine, a celestial ‘Star Trek’-like variation … the list goes on. It caught Karl’s sense of humour and I was very pleased to find that he, of all people, was happy at this seeming lack of respect for the great master!

On the Monday we lunched with John Davies and his family in Kew before rehearsing for our short performance – a duet and two accompanied pieces: all world premieres! I felt reasonably secure in the duet (particularly as I’d written it), but accompanying the great Leister (as very much a second-study pianist) gave me cause for concern. However, we performed to our select audience and all went well. John was delighted, and the following birthday meal (including Karl leading at least three choruses of ‘Happy Birthday’) made for a memorable weekend indeed!