Welcome to this fifth blog considering the content of my new book, The Clarinet. The aim of the book is to present a really thorough discussion of all aspects of clarinet playing, to explain what really happens as we play (much of that scientifically) and how we can learn to develop real control of this wonderful instrument.

In this article we’ll be looking at Finger-work and Dexterity (Chapter 8), an area that so often forms the largest segment of a developing player’s aspiration. “How fast can I move my fingers?” can become the all-consuming aspect of what we label ‘technique’ and although it is indeed central, it is important to remember that it sits, equally, alongside tone production and articulation in the development of a holistic all-round technique.

Of course, we all desire fluent, fast, economical, precise and well-coordinated finger movement – which will allow us to play all that wonderful repertoire. But the development of a really good finger technique will also have a greater and often overlooked impact. The very movement and velocity of our fingers has a significant effect on the actual sound we make too!

So, this chapter looks closely at how we develop our finger work – specifically how we can make our fingers do whatever is required. Maybe the first important point to consider is what actually drives our finger movement? And it might surprise you to learn that it’s not the muscles in the fingers –that’s because there aren’t any muscles in our fingers! The muscles are elsewhere, but that is not important. It’s the brain that drives our fingers. The rhythmic impulse, created in our brains, sending the instruction to the finger to move now is the overriding driver.

As a consequence, it’s essential to feel a strong sense of pulse when working at exercises and studies and connect each physical movement to a brain-generated rhythmic impulse. And there certainly are a lot of exercises to explore! They look at all connected areas like finger location, finger pressure, finger strengthening, control of key-work, and developing fast playing and agility. In the first instance, trill practice is a great way to get fingers moving: practice a trill using each finger at each practice session – especially important to work at little-finger trills. Play them for as long as you can working at evenness and duration. Only very gradually speed them up. Never play a trill faster than you can control well.

Scale practice is also very important and there are many scale exercises to try alongside lots of advice. Enjoy these! Get scales into the positive side of your mind. They really are useful and fun to work at!

There are also some specially written exercises to enable a quick warm-up before a concert or exam.

As you work to speed up your finger-work, remember this very important thought: Fast music is often not about fast fingers but rather about the (short) gap between each finger movement. The ideal manner in which to prepare ‘fast’ music is to practise slowly, ‘programming’ each movement carefully into your memory. Chose the passage you wish to work on, then work at each interval meticulously, thinking about:

1. Which fingers move

2. How they move

3. Any coordination issues

4. Use of oral cavity (voicing) and/or embouchure.

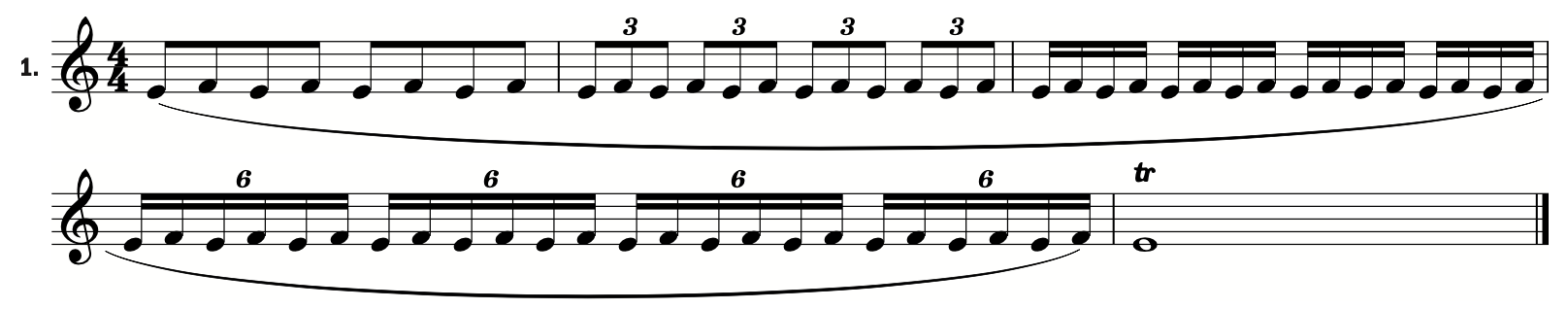

Here’s an exercise to apply to your trill practice:

During practice, make the trilling finger move with a consistent distance from the instrument, rhythmic evenness and make sure no tension builds in the hand, forearm or indeed anywhere else.

In time, and with patience and care (and regular practice!) you should be able to develop the facility to play anything you want.

To learn more, buy a copy of The Clarinet here: https://www.fabermusic.com/shop/paul-harris-the-clarinet-p439043