I originally wrote this article for the September 2009 edition of the ICA Magazine. It turned out that someone had already written a piece that included background to the Britten Clarinet Concerto so instead of potential overlap I provided a completely new item. Here then is this previously unpublished article.

I always get excited when an interesting package drops through the letter box. A couple of weeks ago one such package did. It was the score of the intriguing ‘Movements for a Clarinet Concerto’ by Benjamin Britten, sent to me for review.

Readers may well know of the single movement, of which I have written about in a previous letter, which was recorded by Thea King in the early 90s: Movement for Clarinet and Orchestra on the Hyperion label with the English Chamber Orchestra.

Well now we have a whole concerto.

The story begins in 1941 when Britten was living in New York. The composer had attended a performance of the Mozart Concerto given by the great Benny Goodman. Soon after, the two met and Goodman gave Britten a strong indication that a commission was forthcoming (it would have followed his commission for the Bartok Contrasts) so, virtually straight away, Britten began serious work on the project. In March 1942 however, the composer returned to England and, extraordinarily, the manuscript was impounded by US customs officers as they thought some encoded secrets were hidden within the notation. Some months later, presumably after extremely careful scrutiny, it was eventually deemed safe and dispatched to Aldeburgh. But Britten was now working on Peter Grimes and though he did show some renewed interest in the concerto the following year it was soon filed away – regrettably never again to resurface during the composer’s lifetime.

Nearly fifty years later (in 1990) Colin Matthews (who worked closely with Britten towards the end of his life) completed the single movement which was subsequently recorded by Thea King on her disc of English clarinet concertos. More recently, Matthews had again been drawn to this fascinating work and contemplated reconstructing the complete three movements. The sketches contained nothing that would seem to suggest material for further movements so a more ingenious solution would have to be found. A little known work for two pianos, the Mazurka Elegiaca, which was written at almost exactly the same time as the first movement (the summer of 1941) was chosen as the basis for the slow movement. But what about the third movement? If the piece was to have stylistic cohesion then Matthews needed something else contemporary and appropriate. He went back to the original manuscript and was delighted to discover a substantial sketch for an unfinished orchestral piece (most likely the Sonata for Orchestra which features in a number of Britten’s contemporary letters). It was perfect material for the third movement. And so Colin Matthews set to and soon created the highly effective and engaging work of which I now have a copy on my desk.

The three movements last about seventeen minutes and are scored for clarinet and a large orchestra. The first performance was given by Michael Collins in May 2008 and it is now published by Faber Music. A recording is due out (on the Presto Classical label) in October this year (so should be available by the time you’re reading this!) It’s a great addition to the repertoire. Tuneful and very playable.

Now, some of you may still be wondering about to what exactly the ‘Benn’ part of the title of this letter was referring. Mr Benn is the eponymous hero of a charming children’s TV series. I loved it as a child - especially the music which, as the credits told us, was apparently written by one Don Warren. But in fact it wasn’t. After much careful research I finally discovered that it was written by the well-known saxophone player Duncan Lamont, who wished to keep his duel life as highly-acclaimed jazz artist and composer of children’s TV signature tunes separate. What particularly drew me to the music was the delicious main theme which was beautifully written and scored for bass clarinet and doubled on xylophone accompanied by a small ensemble. Actually Duncan told me he’d originally scored the tune for trumpet, but the trumpet player failed to make the recording session and as there was a spare bass clarinet player about, he re-scored it. Anyway, to cut a long story short I have just arranged and published ten pieces from the series, including the superb title music, for B flat clarinet and piano. (Queen’s Temple Publications, QT 118.) They are simple and absolutely delectable.

So, as we look towards the second decade of the twenty-first century the clarinet repertoire has become the richer through two memorable Bs: Benn and Britten.

Paul Harris 2009

Thurston's other pupil

In the Summer of 2000 I had the great pleasure of meeting James Gillespie, editor of The Clarinet Journal, during the International Clarinet Association (ICA) convention in Oklahoma. James asked me if I would like to contribute a regular column – an invitation that I found both humbling and daunting! The following ‘Letter from the UK’ was first published in May 2009 in The Clarinet Journal, the official publication of the ICA.

I’ve been reading a book about Stowe School recently. Readers may recall that Stowe is a grand and exceptionally distinguished eighteenth-century mansion set in a thousand acres of some of the best landscape gardens in the world, and I used to have the pleasure of teaching there. What really caught my attention (between cricket scores and the comings and goings of members of staff) was a performance of the Mozart Clarinet Quintet in March 1954, given by a promising young clarinettist by the name of Colin Davis. To most, Sir Colin Davis is the international conductor of immense stature. But he began life playing the clarinet and would probably have become a clarinettist of international stature had his interest in the baton not taken him in other directions. I decided to do a bit of detective work to see what I could find out...

Colin Davis began his clarinet studies at the age of eleven at Christ’s Hospital School. He was clearly a highly talented player. For example, the Director of Music (the composer C.S. Lang) organised performances of the Brahms Quintet when Colin was still quite a young teenager; one was at the house of Leslie Regan, a professor at the Royal Academy of Music. Christopher Regan (who went on to become Dean at the RAM) still remembers the performance, ‘Colin was already sounding very professional.’ His playing developed well, for he won a scholarship to the Royal College of Music in 1943 where he studied with the great Jack Thurston. Sir Colin recalls, ‘He was always encouraging: how fortunate I was to have had him as my first professor!’ Fellow student Judy Wilkins (who went on to marry conductor Charles Mackerras) remembers Colin Davis’s enviable ability to transpose, ‘I seem to recall that Colin only had one clarinet at the time, but he could easily transpose A clarinet parts, flute parts, anything really, onto the Bb in an instant!’ Indeed he regularly used to play Mozart Violin Sonatas with fellow student Peggy Gray and gave a memorable performance of the Kegelstatt Trio with Peggy and her future husband, Patrick Ireland, at the Goldsmiths Hall in London. Peggy remembers his wonderful musicianship and sweet tone, but what has remained even more strongly in her mind was the fact that during the course of that particular concert, Patrick’s trousers, to the astonishment of all, fell down!

One Christmas holiday during this period, the young Colin Davis joined another student clarinettist (and near neighbour) on Wimbledon Common to accompany a local choir in their seasonal carol singing. That friend happened to be a certain Pamela Weston and this was not to be the only time they played together. Colin Bradbury, also a student at the RCM, played with Davis around this time too, ‘The RCM supplied players to boost an amateur orchestra for a concert in Maidstone – I found myself playing second to Colin Davis.’

After the Royal College, Sir Colin was drafted into military service and joined the Household Cavalry where he played clarinet in His Majesty’s Life Guards Band. He was stationed in Windsor and the band played regularly at parades and events for King George VI. After being discharged in 1948, Sir Colin became quite a busy orchestral player. He played principal in the Kalmar Chamber Orchestra with either Thea King or Gervase de Peyer as second and, in 1949, toured with the Ballet Russes playing the Nutcracker in, among other places, a very cold Leeds. He also played with the London Mozart Players where he was reunited with his Wimbledon Common duo-partner, Pamela Weston.

Clarinettist Basil (Nick) Tchaikov remembers Colin Davis joining him to play second clarinet at Glyndebourne. It was a Mozart opera and Davis was clearly more fascinated by the conductor than the playing – a sign of things to come. They later performed together again in the New London Orchestra which was conducted by Alex Sherman (a conductor who notably worked with Segovia).

The next few years saw Colin Davis establish an important career as a leading player. He often performed with violinist Erich Gruenberg who said that he played with a lovely clear sound and was indeed an equal of his distinguished contemporary Gervase de Peyer. In 1951, Colin Davis famously gave the first performance of a new Sonatina by the young Malcolm Arnold at the RBA Galleries in London. The second half of the concert included the Brahms Trio. During the summer months, Sir Colin would often attend one of the great (eccentric) institutions of British musical life, Music Camp, where regularly, enthusiasts gather and camp on a hill (near High Wycombe in Buckinghamshire) and play music all hours of the day and night in barns. Particularly memorable were a number of performances he gave of Shepherd on the Rock with his then wife, the singer April Cantelo and, again, The Mozart Quintet. Dartington was also the venue for another performance of the Mozart which Sir Colin played with the Amadeus Quartet. Christopher Finzi recalls a moving performance of his father Gerald Finzi’s Concerto given by Sir Colin with the Newbury Strings (Christopher was a member of the cello section at the time) – the soloist was not phased at all by the fact that Gerald lost his place at one point, and they had to begin again.

Some of the final performances Sir Colin gave were recalled by the writer David Cairns, who heard him play both the Mozart and Brahms Quintets to a group of friends at a house belonging to the famous writer and traveller, Nick Wollaston in 1960. There was also a performance of the Schubert Octet, with the great cellist Jacqueline Du Pré. But as time progressed, Sir Colin’s international career as a conductor grew and flourished and the clarinet remained sadly idle in its case. We’ll never know quite how beautiful that performance of the Mozart Quintet was that March at Stowe; in fact as far as I can tell there are no recordings of his playing. Although we do of course have the wonderful recording of the Concerto played by Jack Brymer and the LSO conducted by Sir Colin – so, perhaps with a bit of imagination...

(In researching this article I have spoken to some wonderful people and I would like to record my thanks and their names here: Colin Bradbury, David Cairns, Christopher Finzi, Livia Gollancz, Stephen Gray, Erich Gruenberg, Peggy Ireland, Anita Lasker, Jean Middlemiss, Gervase de Peyer, Christopher Regan, Nick Robinson, Delia Ruhm, Lenore Reynell, Nick Tchaikov, Pamela Weston and Judy Wilkins.)

A forgotten partnership

In the Summer of 2000 I had the great pleasure of meeting James Gillespie, editor of The Clarinet Journal, during the International Clarinet Association (ICA) convention in Oklahoma. James asked me if I would like to contribute a regular column – an invitation that I found both humbling and daunting! The following ‘Letter from the UK’ was first published in March 2009 in The Clarinet Journal, the official publication of the ICA.

So much of the clarinet repertoire has been born of the collaboration between performer and composer: Stadler and Mozart, Baermann and Weber, Muhlfeld and Brahms are of course the most renowned. But there is a much less well-known relationship that blossomed during the second half of the twentieth century and produced an important collection of clarinet works.

To locate one half of this partnership we need to travel to Scotland, and find a composer whose considerable body of clarinet music richly deserves rediscovery. The composer in question is Iain Ellis Hamilton (1922–2000). And the clarinettist was fellow student and close friend, John Davies. The two young musicians met at the Royal Academy of Music in 1947. At first they formed a clarinet/piano duo, working their way through most of the repertoire. But Iain was there primarily as a composer (a student of William Alwyn, who himself wrote a very effective clarinet sonata) and soon began working on a series of important works for John. These works are now almost completely (but certainly unjustly) forgotten.

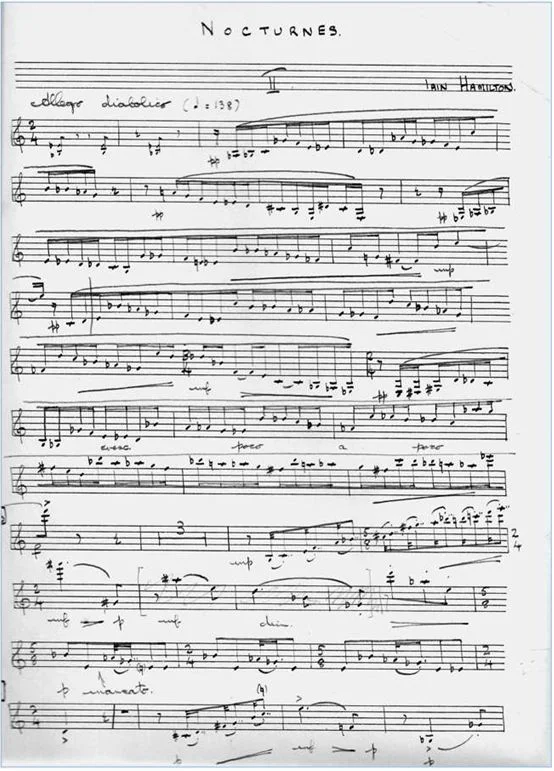

John Davies remembers, ‘He was a tremendously serious and energetic man; worked 48 hours a day. I don’t think he ever went to bed – he couldn’t stop!’ The violinist Nona Liddell found him ‘a little nervy, but very warm-hearted – a true Scot!’ He and John gave recitals all over Europe: Brahms, Ireland, Hindemith, Bax and Weber’s Silvana Variations were among their favourites. I now have the (well-annotated) copies they used in my own library and they offer many insights. A year after their meeting, Iain composed his first work for John; a clarinet quintet. John gave the first performance with the Liddell Quartet (led by Nona Liddell. ‘And a jolly good work too!’ she told me enthusiastically at a recent meeting.). John later broadcast it on BBC radio with the Aeolian Quartet in 1950. Though very interested in the latest serial composers, Iain’s own style at this time was more an amalgam of Bartók, Berg, Hindemith and Stravinsky, giving his music both rhythmic drive and a vivid harmonic colour. Next came his Three Nocturnes for clarinet and piano – perhaps his best known work. John gave the first performance on BBC Scottish radio in 1950 with Iain accompanying. The first London performance was given by Jack Thurston in 1951. They challenge a little, but are enormously worthy of study and performance: atmospheric and audience friendly.

In fact John and Iain regularly gave recitals in Scotland, at the central library in Edinburgh. These concerts were organised by Tertia Liebenthal, who also happened to be a passionate cat lover. Not only did Tertia arrange the concerts, she also reviewed them for The Scotsman, under the pseudonym Zara Boyd (her cat’s name). One evening however, the concert series came to a sudden and abrupt end. She and Iain were in a taxi making for the venue – they were late and John was already waiting uneasily. On the way, Tertia spotted a cat in distress by the roadside. ‘Stop the taxi!’ she demanded, the cat’s rescue now taking unquestionable priority over the concert. Iain was unhappy about this further delay and in his anxiety maliciously announced to the cat lover that ‘John had eaten cats you know, when he was a prisoner of war.’ It was to be their last engagement at the Edinburgh library...

Later in 1951, back in London with cats now forgotten, Iain composed his virtuosic Clarinet Concerto which won the prestigious Royal Philharmonic Prize. Though written for, and dedicated to John, it was Thurston who gave the first performance with the RPO. Jack Brymer gave the first broadcast performance. A Divertimento for clarinet and piano came next in 1953, followed by the Clarinet Sonata, once again dedicated to John, who gave the first performance in Paris in 1954. In 1955 came both a Serenata for clarinet and violin, written for John and Frederick Grinke (displaying a move to a more severe serial style) and the Three Carols for six clarinets, which Iain wrote for a group of John’s students at the Academy: fascinating, imaginative and useful arrangements (published by Queen’s Temple Publications).

In 1961, Iain moved to America where he became Mary Duke Biddle Professor of Music at Duke University in Durham, North Carolina. He was also was composer-in-residence at the Berkshire Music Centre at Tanglewood, Massachusetts (in the summer of 1962). He was to remain in the U.S. for twenty years, writing many wind chamber works among his large output.

There was a long break before Iain turned once again to the clarinet. And it was to be for the last time. In 1974 his opera The Catiline Conspiracy was receiving its first run at the Scottish Opera and, in the pit, playing principal clarinet, was the young Janet Hilton. She was enjoying the work so much that she personally commissioned Iain to write a new work. He wrote her his second quintet, evocatively entitled Sea Music. Janet gave the first performance at the Bath Festival with the Lindsay Quartet. Like all Iain’s clarinet music, the work provides a certain challenge for the performer, but it is more lyrical and rhapsodic, more tonal than some of his earlier works. Janet remembers that the composer took a lot of interest in the rehearsals and seemed particularly pleased with the performance. The London Observer called it ‘an attractive score, full of brilliance and light’. Most of these works are available from Theodore Presser Company.

Looking through the Iain Hamilton manuscripts in preparing this article, I found something amongst them that sent a real shiver of excitement tingling down my spine! I’m working on the Mozart concerto for a performance soon and had been giving quite a bit of thought to the whole business of cadenzas. What I found, most providentially, was a single sheet of manuscript paper on which Iain had composed three intriguing cadenzas for the Mozart; two for the first movement and a beautiful third for the slow movement. I now know exactly what I shall be doing for cadenzas!

The first manuscript page of the second Nocturne. Those who know the work will notice a significant adjustment of metronome mark and various other interesting alterations (including the deletion of three bars).

Four short pieces?

In the Summer of 2000 I had the great pleasure of meeting James Gillespie, editor of The Clarinet Journal, during the International Clarinet Association (ICA) convention in Oklahoma. James asked me if I would like to contribute a regular column – an invitation that I found both humbling and daunting! The following ‘Letter from the UK’ was first published in December 2008 in The Clarinet Journal, the official publication of the ICA.

I’d like to begin with a postscript to my last letter, on the subject of Pauline Juler and Howard Ferguson. I have come across some fascinating letters between Ferguson and Gerald Finzi. The two had an enduring and deep friendship which began in 1926 and ended with Finzi’s death in 1956. Readers will know Ferguson’s delightful Four Short Pieces. But you may not know that, like the Finzi Bagatelles, there were originally five of them! On January 1st 1937 Ferguson wrote to Finzi, ‘there is a set of five short pieces for clarinet and piano which I would like your opinion on: they are very slight, but well enough in their way, I think, and I would like to know whether you think they merit publication…I have asked Pauline Juler to tootle them through with me on the 12th for your especial benefit.’ Sometime between January and June, one of the movements, a ‘bubbly Rhapsody’ was omitted. ‘Not because I don’t like it musically,’ Ferguson wrote to Finzi on June 10th, ‘but because it seems impossible to play without making the most frightful clatter with the keys. Thus the set will consist of Four instead of Five pieces.’ So, did we perhaps lose a piece of our all-too-limited repertoire because Pauline’s clarinet needed a little oil? However, the movement later re-surfaced as the second of the Three Sketches for flute and piano Op. 14 (published by Boosey and Hawkes). But a letter from January 1938 suggests that we may be the poorer for something on an altogether larger scale. Finzi to Ferguson: ‘Pauline Juler is quite right in wanting you to do a Clarinet Sonata. I think you’d do it to perfection, and then there would be no need to revive Stanford and Bax. The little pieces are a signpost.’ How disappointing that he didn’t take the advice.

I try to follow the progress of my old pupil Julian Bliss as best I can, and heard two of his performances recently. I was delighted to hear him play the bittersweet Malcolm Arnold Second Concerto with the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra a couple of weeks ago, in the lavish Birmingham Symphony Hall. I remember working on it with Julian when he was only eight. He gave an astonishing performance even then, with the Huddersfield Symphony Orchestra, attended by Sir Malcolm himself. Just last week, Julian played Weber’s Second with the Ulster Orchestra in Belfast, which I picked up on the radio. It was a real virtuoso presentation with many imaginative moments. So many players worry too much about sticking religiously to the text and whilst Julian didn’t do anything outside the bounds of stylistic decency, there were lots of unexpected and delightful twists and turns causing one to think, ‘Yes! Of course! Why didn’t I think of that?!’.

I always love it when the postman has to ring the doorbell with a parcel too big to fit through the letterbox. And I was especially pleased recently when that parcel was Pamela Weston’s latest book, Heroes and Heroines of Clarinettistry. It’s a collection of many of her writings over the years – absolutely fascinating articles in which Pamela reveals many new insights into composers and works we thought we knew. It’s published by Trafford Publishing (with a Foreword by the ICA’s own James Gillespie) and should be in every clarinettist’s library.

I was judging a concerto competition the other day and was yet again astounded by the standard of young players today. All the musicians were under twenty (some well under) and we had more than adequate performances of Mozart, Weber and even one Nielsen! I remember rushing out to buy a copy of the Nielsen Concerto when I was about sixteen – after hearing a performance on the radio by the great Stanley Drucker. But I never really considered playing it at that time. Now I have my fourteen-year-old pupils wanting to learn it! That’s progress.

Great goings-on in the war years

In the Summer of 2000 I had the great pleasure of meeting James Gillespie, editor of The Clarinet Journal, during the International Clarinet Association (ICA) convention in Oklahoma. James asked me if I would like to contribute a regular column – an invitation that I found both humbling and daunting! The following ‘Letter from the UK’ was first published in September 2008 in The Clarinet Journal, the official publication of the ICA.

A friend sent me an old concert programme recently that really got my antennae buzzing! The concert in question took place on Wednesday, August 19th 1942 at the National Gallery in London. In fact between October 1939 and April 1946, the great pianist Dame Myra Hess was responsible for organising nearly 1,700 concerts at the National Gallery. The war had caused the gallery to close and all the paintings were moved out to a secret location, with the exception of one painting each month which was put on special show. But Myra Hess had the inspired idea of using the space for daily chamber concerts in order to lift the spirits of the beleaguered Londoners. It worked; many thousands came each day to hear the concerts and were indeed inspired by their message of hope.

This particular concert featured, as so many did, Hess herself, on this occasion playing Mozart’s Sonata K.331, followed by the great Serenade for Thirteen Winds. The players involved (under the collective title of The London Wind Players) reads like a music-historian’s dream. The two clarinettists were Pauline Juler and George Anderson. Pauline is well known for her early and impressive performances of the Finzi Bagatelles which inspired the composer to write his Concerto for her – but she never played it. Pauline was about to get married and she decided to give up playing the clarinet for good. She was the daughter of an Harley Street doctor and, by all accounts, a musician of charm and wit. But she did suffer from frequent memory lapses; ‘my forgettery’ as she called it. Pauline Richards, as she became, lived out her life in the delightful Suffolk village of Pakenham and died in 2003. (More about Pauline later.) The other clarinet player was George Anderson, a pupil of Henry Lazarus, who although seventy-five in 1942, was still teaching at the Royal Academy of Music. In fact he remained there until his death in 1951 and taught, among many others, John Davies and Georgina Dobrée.

The two bassett horn players were Walter Lear and Richard Temple-Savage. Lear, like so many clarinet players, enjoyed a very long working life. He was professor of clarinet at Trinity College of Music for fifty years and played, intermittently, at Covent Garden for seventy-one years! It is thought that he might have given the first performance of the little known York Bowen Phantasy Quintet for Bass Clarinet and String Quartet. (Readers will find much concerning Temple-Savage in my article of May 2005.)

The horn section appearing on that memorable concert date also boasted some very well known names: Dennis Brain, Norman del Mar and Livia Gollancz. Livia (daughter of the publisher Victor Gollancz and still very much alive) was a direct contemporary, fellow student and friend of Sir Malcolm Arnold.

Talking of Sir Malcolm, the Third Arnold Festival is just around the corner, in mid October. As usual his clarinet works will be represented: this time it’s the late and compelling Divertimento for two clarinets (played by two of my pupils, Charlotte Swift and Jonathan Howse) and the miniature Fantasy for Clarinet and Flute (written about the same time as his haunting score for Whistle down the Wind and bearing many resemblances).

And so back to Pauline. A number of years ago I was sent an interesting work, which I’m ashamed to say has lingered in my ‘awaiting action’ pile for some time. It’s a big neo-romantic clarinet sonata by Charles O’Brien. I finally played it the other day and discovered it to be very much worthy of attention. O’Brien was a Scottish composer born in 1882 (two years before Brahms wrote his Opus 120 sonatas). Though written about fifty-five years later in 1939 it is in fact quite Brahmsian in style (or perhaps ‘Stanfordian’) and is in the wonderfully appropriate clarinet-friendly key of E flat. It turns out that O’Brien first sent it to Pauline for her recommendations. She evidently suggested a major revision of the final movement and that is now the published version (The Hardie Press, Edinburgh). But she didn’t give the first performance. That privilege was entrusted to Keith Pearson (another John Davies pupil) who recorded it for the BBC in 1966. There’s nothing too technical in it, so if you have a place for a big romantic sonata, do give this a go!

Summer news

In the Summer of 2000 I had the great pleasure of meeting James Gillespie, editor of The Clarinet Journal, during the International Clarinet Association (ICA) convention in Oklahoma. James asked me if I would like to contribute a regular column – an invitation that I found both humbling and daunting! The following ‘Letter from the UK’ was first published in May 2008 in The Clarinet Journal, the official publication of the ICA.

Readers will be sad to hear of the death of Georgina Dobrée. I had a couple of lessons with Georgina when I was at the Academy; she helped me with some French music – one of her speciality areas – and I well remember her useful practical advice. Like my own teacher, she was a pupil of George Anderson, though she originally entered the RAM as a first study pianist. After studies in London she went to Paris and had lessons with the legendary Gaston Hamelin, which gave her weighty insights into the Debussy Rhapsodie and other French music. (Indeed, her parents had French Huguenot origins which strongly affected her empathy with French music.)

Georgina was a real enthusiast and each of her enthusiasms were strongly cultivated. She championed the basset horn, uncovering and commissioning much new repertoire for it; she championed rarer repertoire and through her various connections in the publishing world, saw to it that these works were published (and remained so); she championed early clarinet music – her recordings of the Molter Concertos, for example, were the first available; and she commissioned much new music from contemporary composers. Her particular interest in Czech music and composers resulted in many new works: Pokorny, Rybar, Benes, Janovicky, to name but a few. And many composers wrote music for her, among them Gordon Jacob, Elizabeth Lutyens, Maurice Pert and Paul Drayton.

Of all Georgina’s passions my own favourite is her ‘rediscovery’ and subsequent first recording of the terrific Coleridge-Taylor Quintet. It was recorded on her own label, Chantry Records, and boasts a wonderful reproduction of one of her artist mother’s collages on the front of the sleeve. Though a difficult work, the Quintet is now beginning to receive the attention it so richly deserves.

She was also a bit of a nomad – often moving house, and from one part of the country to another. She loved to have input into their design (clearly a strong link with her mother). I recall particularly a house she had for a while in north London with a most imaginative shape and interior plan. Doors everywhere but no corridors and passage ways (she felt these wasted space!). She would often have parties – I attended one or two – to which she would invite musicians and people from various areas of academia; she knew many fascinating people. The clarinet world will miss her.

Moving on, I’d like to bring two new CDs to your attention. Semplice – From beautiful beginnings is the title of a charming and highly imaginative new CD from Victoria Soames and Clarinet Classics. It explores music both written and arranged for beginner players. Among the many arrangements featured, there is music by Schumann, Debussy and Ravel, Kabalevsy and Bartok, and among the many original works there is music by Howard Ferguson, Dorothy Pilling (who was on the staff of the Royal Northern College of Music for many years and wrote delightful music) and Christopher Gunning (composer of the theme tune to the TV series Poirot). There are some of my own pieces too. I’ve always hugely enjoyed writing for young players. The restrictions set intriguing challenges, and the joy of helping emerging players to connect with their developing musical imaginations is enormous.

Also new to the Clarinet Classics label is a disc of the excellent David Campbell playing three concertos. The CD includes two concertos by British composers and one by an American who has lived over this side of the Atlantic for the past forty years. Agnostic by Graham Fitkin represents a work of great power and depth. Written in an accessible tonal style it is an important addition to the repertoire. Each movement of the Concerto by Carl Davis, subtitled Hungarica, paints a picture of some aspect of Hungarian life, and the recording is completed by the wonderful Finzi Concerto.

Recently, I had the great pleasure of spending the afternoon with the celebrated couple John Dankworth and Cleo Laine. Though both now in their eighties, they are full of unbounded energy and tremendous zest! John told a wonderful story. He had given a performance of the Copland Concerto with the Morley College Orchestra conducted by Lawrence Leonard. Unbeknown to him, Malcolm Arnold was in the audience. Many years later, John put Malcolm up for a Wavendon Award. On receiving the award from John himself, Malcolm turned to the audience and said, ‘I remember John screwing up the Copland Concerto with the Morley College Orchestra in 1967’. Malcolm at his most disarming! John told the story with relish.

And finally, talking of Malcolm Arnold, I’ve just put the finishing touches to the programme for the third Arnold Festival, to take place in Northampton in October. The enigmatic but highly engaging Divertimento for two Clarinets (published by Queen’s Temple Publications) is among much of Sir Malcolm’s music to be heard this year. In the meantime, enjoy the remainder of the summer!

Nonagenarians anonymous

In the Summer of 2000 I had the great pleasure of meeting James Gillespie, editor of The Clarinet Journal, during the International Clarinet Association (ICA) convention in Oklahoma. James asked me if I would like to contribute a regular column – an invitation that I found both humbling and daunting! The following ‘Letter from the UK’ was first published in March 2008 in The Clarinet Journal, the official publication of the ICA.

John Davies, my teacher and mentor, was ninety the other day. A small party was organised to celebrate this momentous event and pupils and friends assembled at his daughter’s house in Kew. Karl Leister flew over from Berlin and, together with myself, Duncan Prescott (who plays with the London Sinfonietta) and Linda Merrick (vice-principal of the Royal Northern College of Music), we performed a special ‘Happy Birthday’ piece I had written a little while ago. Karl also gave a wonderful performance of the beautiful Reger Romance. Amelia Freedman, director of the Nash Ensemble and another of John’s illustrious pupils, was also there and entertained us with fascinating behind-the-scenes stories of the Nash and some of its many commissions. It was a memorable evening.

Another clarinet-connected nonagenarian is the composer Arnold Cooke. I’ve just looked through all my Letters from the UK and was surprised to find that I’ve very rarely talked about Cooke. So I’m going to make amends! Cooke died in 2005 at the age of ninety-nine. I’m sure readers know the wonderful (and slightly Hindemithian) Sonata written for Thea King but I wonder whether you also know quite how much other music he contributed to the clarinet repertoire? Do you know, for example, his Trio, Quartet and Quintet? Have you come across his set of songs for voice, clarinet and piano, the Alla Marcia for clarinet & piano, the trio for clarinet, cello and piano, or perhaps his Septet for clarinets? Then there’s a Prelude & Dance for clarinet and piano and his two clarinet concertos? Quite a collection!

I actually had the pleasure of playing the Sonata to Cooke himself. He was an extremely self-effacing man, very shy and quiet. The Alla Marcia was his first clarinet work, written in 1946. It’s a charming little piece lasting less than five minutes and a useful concert item. The First Clarinet Concerto came next. Written in 1955 it was first performed by Gervase de Peyer. The delightful Three Songs of Innocence was composed for the Clarion Trio – the clarinettist was none other than Pamela Weston – who gave the first performance in 1957. If you don’t know these songs (and have a soprano and pianist to hand) waste no time in acquiring a copy! I’ve played the Suite for Three Clarinets (1958) on many occasions. It’s a very effective work in four short movements. Stephen Waters – the clarinettist much associated with Malcolm Arnold’s Wind Quintet – played in the first performance. Thea’s Sonata came next (in 1959). It’s a very playable work, full of very lyrical writing and concluding with a highly energetic tarantella-like dance movement. The Quintet was commissioned by The Lord Mayor of London for the first City of London Festival in 1962. Again it was Gervase who gave the first performance, though sadly now it is rarely played. In three movements and a little over seventeen minutes it a work well worth exploring. In 1965, Cooke wrote a trio for clarinet, cello and piano for the Hilary Robinson Trio (clarinet, Rachel Herbert); the Septet for Clarinets written for the London Clarinet Septet came in 1971, followed by a lively Quartet for Four Clarinets in 1977 (published by Emerson Edition). The short (and highly accessible) Prelude and Dance was commissioned by Jack Brymer for a new collection of teaching pieces published by Weinberger in 1980 and, finally, the Second Clarinet Concerto was written for Stephen Bennett in 1981. And that list doesn’t include various wind chamber works that include the clarinet. It’s an impressive and an important contribution.

My final nonagenarian is Howard Ferguson, whose centenary it is this year. Ferguson died in 1999, aged 91. I’m sure you’ll know his Four Short Pieces – short and charming and each based on a mode rather than a key. But do you know his arrangement of three pieces by Schumann published by Boosey and Hawkes (in 1976) as Three Duos? Karl Leister introduced them to me recently (and they are included on his new CD, Karl Leister plays Robert Schumann). They are absolutely exquisite and should feature in every clarinet recital this year. Here’s to a wonderful summer of discovery!

Nash, Browne and 303 fingerings

In the Summer of 2000 I had the great pleasure of meeting James Gillespie, editor of The Clarinet Journal, during the International Clarinet Association (ICA) convention in Oklahoma. James asked me if I would like to contribute a regular column – an invitation that I found both humbling and daunting! The following ‘Letter from the UK’ was first published in December 2007 in The Clarinet Journal, the official publication of the ICA.

The Nash Ensemble will be well known to musicians and music lovers all over the world. They are, and have been for many years, one of the greatest chamber ensembles. You will therefore be delighted to learn that their newest CD (Hyperion, CDA67590) features the wonderful Clarinet Quintet by the English composer, Samuel Coleridge-Taylor, who was born in London in 1875. Coleridge-Taylor studied at the Royal College of Music where he was a pupil of Charles Stanford and a friend of fellow student and composer William Yeates Hurlstone (of Four Characteristic Pieces fame). He couldn’t resist his teacher’s challenge that ‘no one could write a clarinet quintet without displaying some Brahmsian influence’. Indeed, had Stanford set himself the same challenge when writing his own clarinet sonata he would have failed miserably! It pays some considerable obeisance to Brahms. But not only did Coleridge-Taylor meet the challenge, he also wrote a work of scintillating brilliance. Coleridge-Taylor himself openly admitted that his favourite composer was Dvorak and this is indeed the clarinet quintet that Dvorak never wrote (or at least, if he did, it has not yet been found!). When presented to Stanford, the master exclaimed, ‘You’ve done it, me boy!’ It’s a long work – just a few seconds short of thirty minutes – skilfully crafted and full of glorious melody and sparkling rhythms. Sadly, like Hurlstone, Coleridge-Taylor died young, at the age of thirty-seven; what might he have achieved had he lived longer? On this recording, Richard Hosford plays the work beautifully.

Talking of Brahms, real aficionados may know of a short book about the Symphonies written in 1933 by Dr Philip Browne. Readers may remember my mentioning a delightful little work, famously recorded by Jack Thurston, and called (somewhat quaintly) A Truro Maggot. The composer was the same Philip Browne who, I was delighted to discover, was the first Director of Music at Stowe School where I taught and was Head of Wind and Brass for a number of years. I well remember working on A Truro Maggot with Julian Bliss (who loved the title) when he came for his lessons at Stowe. I had no idea of the connection at that time. And a second coincidence: a couple of weeks ago I had lunch with an old professor of mine from the Royal Academy of Music, who very kindly sent me home with his personal copy of ‘the Maggot’ signed by the composer. Being the proud possessor of a second and autographed copy I rummaged through my CD collection and found the recording. Listening to it, and following the score, I noticed that curiously the pianist Myers (Bill) Foggin misses out most of the left-hand notes! So if anyone out there wants to record this witty little gem (with all the left hand notes intact) it would be, in one sense, a world premiere!

On a final note, I wonder whether readers know of what has become something of a clarinet classic – the little blue book entitled 303 Clarinet Fingerings (and 276 trills) by Alan Sim. There are no end of surprises and fascinating suggestions for every note on the instrument up to the G above altissimo G. How many fingerings do you know for altissimo G? Including trill fingerings, Alan has thirty-four! There are fifteen fingerings for C above top C, and twenty for top C. The book also includes any amount of helpful and insightful advice on fingering, plus a number of witty limericks to lighten the way. There was a possibility that this invaluable little book may have gone out of print, but after some discussion with Alan I am delighted to report that Queen’s Temple Publications will be taking over publication from 2008. Like many teachers, I always train my pupils to think about and explore fingering creatively. Many players learn their fingerings from a first tutor and for ever after consider these to be the correct and only ones possible. Alan certainly dispels that line of thinking instantly! It is a little gem of a book that ought to be in every clarinettist’s pocket (it would fit too!)

A tribute to Thea King

In the Summer of 2000 I had the great pleasure of meeting James Gillespie, editor of The Clarinet Journal, during the International Clarinet Association (ICA) convention in Oklahoma. James asked me if I would like to contribute a regular column – an invitation that I found both humbling and daunting! The following ‘Letter from the UK’ was first published in September 2007 in The Clarinet Journal, the official publication of the ICA.

In preparing for my previous ‘Letter’, little did I realise that my conversation with Thea King would be the last I would ever have. She sounded a little tired and indeed mentioned that she might be going into hospital, but as we chatted about Jack Thurston and Richard Rodney Bennett, she was one hundred percent on the ball and her spirits seemed high. She died less than two weeks later. The memorial evening at the Royal College of Music was a moving but life-enhancing affair. Many British clarinettists were there, as well as friends from other branches of the music profession who had known and loved Thea. We were reminded of the breadth of her interests: cows, the countryside and slightly risqué poetry; much written by herself! There were affecting speeches by Colin Lawson and Neil Black, oboist and fellow English Chamber Orchestra player. Her own choice of music for the occasion included a number of songs by Schubert and Schumann, and we also heard part of her recording of the terrific but rarely played Benjamin Frankel Quintet. And so we were reminded of her continued championing of clarinet works by a broad range of British composers. Her recordings are just part of the very special legacy this great musician has left.

Remaining with that wonderful generation for a moment, I was delighted that one of my young pupils, Ben Westlake (aged 14) recently had a lesson with the great Gervase de Peyer (aged 81!). Gervase was on sparkling form and a few days later did us the honour of attending Ben’s performance of the Weber Concertino at London’s Cadogan Hall with the Southbank Sinfonia. My teacher and mentor Professor John Davies also came along and it was great to see the two old friends reunited.

I briefly mentioned the new Naxos East Winds CD of Malcolm Arnold Wind Music in my last letter. I hope readers will have managed to purchase a copy by now. It is a treasure trove of goodies, with many first recordings: the wonderful Quintet Op. 2 and the Grand Fantasia for flute, clarinet and piano, for example. I’m delighted (but not surprised) that the Wind Quintet is already becoming a ‘standard’ in the repertoire. And speaking of Malcolm, the Second Arnold Festival is almost upon us. This year the festival includes a whole recital devoted to the composer’s wind chamber music and young Ben (mentioned above) will be playing the clarinet part in that gorgeous early song for voice, clarinet and piano Beauty haunts the woods (words by Ruth Arnold) in a talk about Ruth – Malcolm’s elder sister – who was a poet and great inspiration to the young composer.

I’d also like to mention another new CD (Camerata CMCD-28103), of Karl Leister playing seven of Lefevre’s lovely Sonatas. Karl is using the edition prepared by myself and John Davies (the first five published by Oxford University Press, and No.s 6 and 9 – really quite a large-scale work – by Ricordi). John and I went out to the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris to research the manuscripts for this edition a couple of years ago and I well remember the helpfulness of the French librarians. Karl, as you would imagine, plays the sonatas beautifully; the purity of his sound is ideal in projecting the deeply lyrical nature of the clarinet writing. I do most strongly recommend this disc.

Three for two

In the Summer of 2000 I had the great pleasure of meeting James Gillespie, editor of The Clarinet Journal, during the International Clarinet Association (ICA) convention in Oklahoma. James asked me if I would like to contribute a regular column – an invitation that I found both humbling and daunting! The following ‘Letter from the UK’ was first published in June 2007 in The Clarinet Journal, the official publication of the ICA.

We clarinet teachers often play duets with our pupils. Among the ever-increasing duet repertoire, we all know the three Crusell duets, those of Mozart and Poulenc and all those grandiose, almost symphonic works that appear towards the end of the similarly grandiose and symphonic Klosé tutor. But I’d like to draw readers’ attention to three interesting duets by British composers that may well be less familiar. The first is by Alan Frank – the other half of the Thurston and Frank Tutor. Frank was Head of Music at Oxford University Press for many years and was a clarinettist himself. I had the great pleasure of meeting Alan a few years before he died. He was a delightful, lively and highly articulate musician, editor and writer. We met at a colourful Chinese Restaurant in London and enjoyed a very engrossing conversation about the composer William Walton (who he had edited), Phyllis Tate (who he had married) and Frederick Thurston (his teacher). The duet in question is called simply Suite for Two Clarinets, which was somewhat of a landmark work. Aside from Poulenc, composers hadn’t taken up the clarinet duet as a viable genre. This Suite changed that, and the number of works for teaching, amateur and professional use thereafter is of course very significant. It was composed in 1934, recorded in 1936 and dedicated to Thurston and Ralph Clarke who sat next to each other in the BBC Symphony Orchestra for many years. It is highly melodic, humorous and, in places, quite jazzy. An entertaining and very useful piece.

In the 1960s, Thea King and Stephen Trier both played in the Vesuvius Ensemble, a chamber group that was originally set up with the specific purpose of giving performances of Schoenberg’s Pierrot Lunaire. The ensemble was in residence at the famous Dartington Summer School in the summer of 1967. Also teaching on the course was the young composer Richard Rodney Bennett. Thea woke up one morning and discovered some sheets of manuscript paper on the floor, which someone had slid underneath her bedroom door. That someone was Richard Rodney Bennett, who had composed a delightful four-movement work for her, literally overnight! This original version of Crosstalk was in fact written for two basset horns but published later in a more practical version for two clarinets. Thea, who recorded the work (in its first incarnation) with fellow basset horn player Georgina Dobrée, is quite adamant that the piece loses something in translation, but nevertheless we still have this extremely effective and highly skilfully written work readily available. If you don’t know it, don’t delay in purchasing a copy!

The third duet is by Sir Malcolm Arnold. In the late seventies Malcolm had a severe mental breakdown and it seemed that he might never compose again. After two and half years in a mental hospital things looked bleak. However he was nursed back to health by his devoted carer Anthony Day who encouraged Malcolm to begin composing again. Anthony was well rewarded: all sorts of orchestral, chamber and instrumental works date from this final period of Malcolm’s compositional life. In 1986 Malcolm wrote his last symphony (his ninth) and, two years later (in July 1988) he produced a very quirky and arcane little Divertimento for Two Clarinets. I asked Malcolm many times if he wrote it for anyone in particular, but it would seem that he simply wrote it because he wanted to. There are many similarities between the six movements of the Divertimento and the introspective Mahler-inspired 9th Symphony. Both combine a certain wit and lyrical melody with moments of darker and almost other-worldly writing. It’s a fascinating little piece and well worth exploration. With a little explanation, audiences find it both intriguing and compelling. The chamber ensemble East Winds has just brought out a wonderful new all-Arnold wind music CD (on the Naxos label) that includes the Divertimento as well as the world premiere recording of the Wind Quintet Op.2.

Happy duetting!